Written February 17, 2017

I recently ran a user feedback survey that exposed a flaw in my thinking — and resulted in a completely unexpected product change.

The survey’s intended goal was to aid in developing a deeper understanding of the various use cases customers have for Geocodio and features that might help them more efficiently complete those activities. I also put in a general feedback field for open ended thoughts on the service, positively or negatively.

Delightfully, there were quite a few happy users who put comments that are the survey equivalent of a yearbook note from a best friend in high school: something you’ll keep a mental note of and return to on a tough day. “This is by far the best, easiest geocoding service I have used.” “UX is a delight.” “Awesome, stable service.” Ahh, I thought to myself, satisfied. Happy users. I have done my job.

But that glow evaporated by the time I’d gotten through all of the responses. There were a couple of not-so-positive points of feedback, ranging from feature improvements to issues with our customer service. As a business that’s run by its co-founders on nights and weekends, we know our customer service response times could be a lot faster. But one in particular hit me hard:

“…we were completely unable to access your service. Repeated tries, online chats, emails were never returned. Our client finally pulled back the work from us since we were unable to access your site. Not only did it cost you, but it cost us as well. What we promised could never be fulfilled.”

Arrow meet chest.

And like that, all of the happy customers melted away, and I was reminded that you’re really the only one who keeps score of what percentage of your customers are happy and knows if it “balances out” at the end of the day. For the people who have a bad experience, that’s their experience, period.

Seeing that email, I immediately recalled the situation. My co-founder (also my husband, and also the only other person who works on the business) and I had been driving back from Christmas vacation that day. We had only intermittent access to Intercom due to where we were driving. We saw the messages come in but were unable to reply and made a mental note to reply when we got home. Which we didn’t, because it was late. We were tired. We failed to reply.

We failed.

We failed in our responsibilities as business owners. We failed the customer. We even failed their customer. We lost their business and, more importantly, their trust.

And it was all for a reason that seems so clearly illogical in retrospect.

The customer had gotten stuck in the abuse filter in our sign-up process, which prevented multiple accounts from the same IP address. We had some issues with people abusing our freemium model just after we launched, and this was a deliberate, carefully considered solution. We didn’t want someone just creating five accounts to max out our free tier across multiple accounts, after all.

But that was three years ago, and our business has changed a lot since then. We’ve scaled up subscriptions, transforming the freemium level to a only small percentage of revenue rather than the entire pie. We’re also receiving more sign-ups from larger organizations and companies who need to have multiple accounts rather than the freelance and dispersed developers that made up our initial users. Not realizing that the business had changed so much since we originally implemented this as the solution, we handled legitimate users trying to create multiple accounts on a one-off, manual basis and had no intentions to change it.

But that tough piece of feedback kept gnawing at me, and as I manually created more accounts for people whose coworkers had already signed up, it dawned on me that there was a greater mistake I was making in addition to not adapting the practice to our current customers: I was willing to put legitimate customers through a sub-optimal sign-up experience in order to thwart people who would abuse the system. The fear of that lost revenue loomed greater than the possible gain of a legitimate, happy customer with a seamless signup experience.

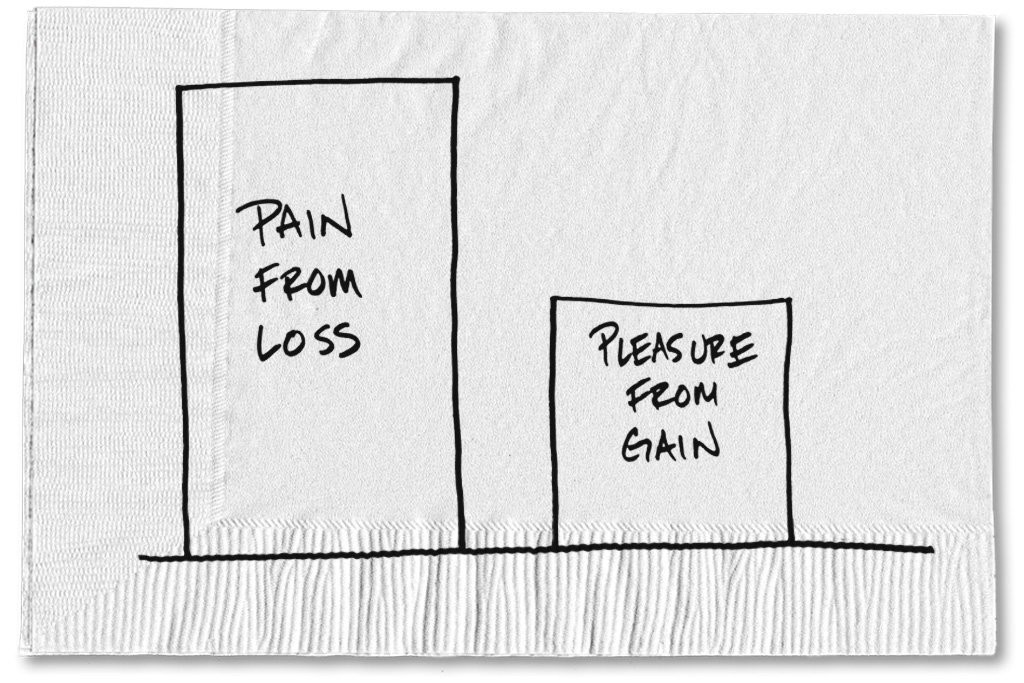

In other words, I realized I was falling prey to the cognitive fallacy of loss aversion that Daniel Kahneman explains in Thinking Fast and Slow: the fear of loss is greater than pleasure of potential gain. As Carl Richards illustrated in The New York Times, it’s a powerful force:

In a recent interviews, Mr. Kahneman shared the usual response he gets to his offer of a coin toss:

“In my classes, I say: ‘I’m going to toss a coin, and if it’s tails, you lose $10. How much would you have to gain on winning in order for this gamble to be acceptable to you?’

“People want more than $20 before it is acceptable. And now I’ve been doing the same thing with executives or very rich people, asking about tossing a coin and losing $10,000 if it’s tails. And they want $20,000 before they’ll take the gamble.”

Our free tier, which gives every user 2,500 free address-to-latitude-and-longitude lookups per day, only works out to the equivalent of $1.50 worth of usage. Additional addresses beyond that are $0.50/1,000. So it’s still a fair amount of work someone would have to do to exploit that system — say, by creating multiple accounts and splitting up their file into dozens of smaller files with 2,500 each — only to save a handful of bucks.

That also means that, from a business perspective, our effort to prevent the loss of, say, $5 here and $10 there, has caused us to miss the gain of several hundred or even thousands of dollars. Thinking back to the user that we so spectacularly failed, we promised them a solution, and unintentionally held it just out of their reach… all in the effort to prevent a small percentage of people from abusing the freemium level. It just didn’t make any sense.

So tonight, we got rid of that one-account-per-IP filter. It was frustrating our users, causing unnecessary amounts of customer support time, leading to lost business and thus costing us money on a net basis.

When I sent out the feedback survey, I never expected this to be the first product change we’d end up making. I never expected to loosen our abuse filtering. It’s a counterintuitive solution, but as the work of Kahneman shows, sometimes what’s intuitive isn’t really right after all.